Late last year, within a small darkened screening room in the bowels of London-based visual effects company MPC’s studio, Iron Man director Jon Favreau invited a handful of journalists to a presentation of scenes from his upcoming live-action adaptation and reboot of Disney’s The Jungle Book.

However, to call it ‘live-action’ would be something of a misnomer.

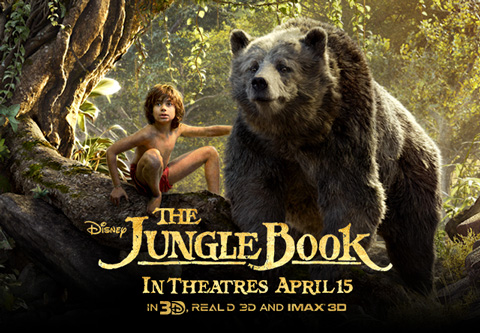

Using motion-capture and digital creation techniques pioneered by James Cameron’s Avatar, Favreau has set out to create a photo-real tale – without ever stepping foot in a jungle. In fact young Neel Sethi, who plays Mowgli in the film, is the only real object on screen for a large percentage of the movie; every single frame digitally crafted by artists from special effects studios WETA and MPC, and hand-made to suit the film’s larger-than-life narrative.

“So often visual effects are seen as a thing where you just put it in a computer and it comes out,” Favreau admitted to his audience, with some note of sadness. “This is the most handmade film I’ve ever done, it’s just the tools are different. It’s like a mosaic, with everyone painting each individual tile.

“It wasn’t a hand-off, like ‘Here’s a movie, put the animals in’. It’s not that. The visual effects artists were there on set.”

The presentation started with a simple, short series of animations showing exotic birds flying onto and interacting with a branch in the jungle. The first test footage, clearly older, had an odd-sense of the uncanny valley – the bird’s motions realistic, but the actual render and digital model of the first bird looking ever-so-slightly like a videogame.

The second test footage, on the other hand, elicited a gasp from the captive, cynical audience. A startling blue bird flew in, looking like a deleted clip from a BBC One documentary, and earning a smug grin from Favreau himself. If there’s one thing for certain, the whole experience looks effortlessly fluid in motion.

The journalists were then treated to the first genuine clip from the film itself. The presentation opens on a watering hole, where we first meet Sethi’s Mowgli – an inspired piece of casting, looking like he simply jumped out of the original Disney feature. The focus, however, is on the introduction of Idris Elba’s Shere Khan. Stalking around the animals of the watering hole, sniffing out the “man-cub” in the midst, and threatening his life all in a handful of minutes, it’s a menacing set-up that still visually errs too far on the side of ‘only almost photo-real’.

The animals themselves look close enough that a half-hearted squint will see them become indistinguishable from the real thing. An obvious effect, too, is Favreau’s inspired focus on real animal behavioural patterns, the director making a point of not simply mapping animal features to a motion-captured human face.

The technique pays off in spades, with the film working at its best when the frame is filled entirely by digital creations. It is in the blending of Sethi’s Mowgli and this digital world that the aesthetic doesn’t wholly pay off. It’s close, closer than perhaps 90 percent of big-budget Hollywood movies, but still glaringly obvious.

Conceptually approached like an animated movie, Favreau expanded that “this process looked a lot like a Disney or Pixar movie in the beginning; it was all pencils and animatics”.

“Except we went to a motion-capture stage where I could direct the camera, the actors, and we had built sets that were, you know, the same shape as what you saw … And then we cut the movie together, and from then that’s where we started filming the live action segments – so we had to redo the movie again.

“I felt like I could direct it like I direct a regular movie.”

The final two sequences were introductions to two of the original animation’s fan-favourite characters; Baloo and King Louie. Bill Murray’s Baloo elicited cheers, clapping, and laughter from the audience, whilst Christopher Walken’s Louie was a silence-ushering presence.

Much of the film has notably been ‘scaled-up’, a subtle effect that sees Mowgli’s perilous position seem all the more lonesome and dangerous as the jungle and its inhabitants literally tower over him. But King Louie takes this concept to a whole other level, with Favreau and the visual effects teams drawing on a prehistoric ancestor of the orangutan to create an enormous, overbearing creature with the unmistakeable, distinctive voice of Walken lending a gloriously intimidating atmosphere to his scenes.

However, both brought up a fair question of just how much of the famous score will be featured in this darker interpretation. A balancing act that, Favreau says, was hard to accomplish: “It’s a tricky thing. Because you don’t want to make it a musical, because the moment it becomes a musical you lose an emotional connection. I think as audiences, generally, you want to feel like you’re emotionally invested.

“You don’t want to feel like you’re pulling the rug out from under the audience, but then again, these songs are classics. And so as a director, the one area I’m responsible for, where there’s no redundancy, is tone. If you like the tone of a film, that’s something you can squarely put on the director.”