“Are you lost? Textiles is upstairs.” That’s what an engineering teacher in college said to Renee Mae Lawati, 20, when she entered a classroom full of boys.

For two years she had to prove to her classmates, who had a bet on how long she would last before she would quit, that she was a capable student and who was not here to learn a new hobby.

Lawati, who is now in her second year in aerospace engineering, runs the engineering society and helps a lot of women to look for work placements and get the support they need.

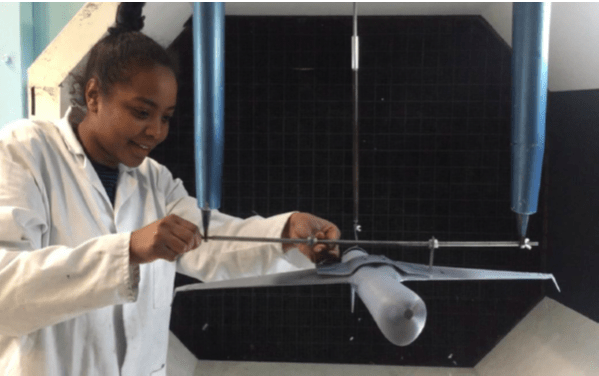

Her childhood dream was to become a pilot but because of her weak eyesight she had to find an alternative: “If I can’t fly it I might as well make it,” she said.

This year, the industry has made some huge first steps by choosing Jody Singer as its first female director of Marshall Space Flight Center (test site for NASA’s rockets) in the US, and by appointing Hayaatun Sillem as the chief executive of the Royal Academy of Engineering in the UK.

Sillem said: “It simply can’t be right that the UK engineering workforce is still 91 per cent male.”

According to the Women’s Engineering Society (WES) the UK has the lowest percentage of women in the industry in Europe (nine per cent) while Latvia, Bulgaria and Cyprus are near 30 per cent.

India has over 30 per cent of female engineering undergraduate students, whereas the UK only has 15 per cent.

“I wanted to study art as well but it conflicted with the teaching block so I couldn’t do it.

“I either had to focus on maths or art. I’ve always been pushed to do textiles, home economics or something creative,” said Lawati.

She knows that the future will not always be easy and she will fight the stigmas.

Lawati started studying engineering in college with no background in the field unlike most of her fellow male students.

For the end of year they all had a massive test and had to make a robot in individual work and people kept saying she was going to get help from the guys because she was the only girl.

“Everyone kept asking me why I was doing engineering and said that I could do something else because I am a girl.

“Hearing all that kind of stuff did put me down at first but because I am a girl I need to prove myself more that I can do it. All the guys were in one corner and I had one corner to myself so I felt a little bit isolated but I wanted to prove myself to them that I don’t need their help.

“They thought I physically couldn’t do practical classes because I was ‘weaker’ than them,” Lawati said.

Studying engineering is hard both physically, and mentally, through calculating complex mathematical and physics problems.

But being a female student in this field adds some difficulty to study engineering.

Not only do they have to keep up with their grades and classes but they also have to prove themselves to all their male peers.

Many female students experience gender discrimination within their class.

Third-year aerospace engineering student Hishma Shaukat says it is a male ego issue more than anything else, and guys can be intimidating and look down on girls, assuming they don’t know what they’re talking about.

She said: “Especially in group projects. Usually I don’t get listened to and when I do somebody will try to claim the idea was theirs.”

Shaukat, 20, had to learn how to stand up for herself and speak up when she was “ditched last minute” by her team who tried to claim they worked equally on a project.

She finally got the grade she deserved and the boys came clean to their lecturer about not doing the work.

In the UK women can get financial assistance like scholarships or bursaries to study engineering and other male-dominated industries.

When first-year aerospace engineering student, Liv Retallack, was applying to universities she heard that she could get one of these and it was not based on her grades.

“I don’t think it is fair especially if a guy has better grades than me. I think he should get the same opportunity to get this scholarship or bursary,” the 18-year-old student said.

There is this idea that female students who want to study engineering will get a place at any university because of their gender and not because of their applications.

When Retallack was writing her university applications her personal tutor from school told her that she would get in anywhere because she could play the “girl card”.

That angered her because it seemed that it was not only her teacher’s mindset but most people around her.

Lawati was disappointed when her family and teachers told her they were not surprised she got in the five universities she had applied to as she was “obviously accepted because I am a female,” she said.

“Rather than stand out because I am a woman I think I have to stand out because there are so many people who want to do this because it is such an interesting field,” said Retallack who fell into the engineering world during secondary school.

Head of Department of Aerospace and Aircraft Engineering at Kingston University, Peter Barrington, said: “We put a lot of effort into ensuring that our students are employable and this includes ensuring they have a range of skills and behaviour that will support them through their career.”

The University currently has visiting professor Dawn Childs who is of the WES to help address some of the specific challenges facing female university students.

“I agree that it is not fair to judge female engineering students/junior engineers because there is a perception that it is easier for them to gain a place to study.

“This perception is not unique to females, many companies are trying to increase the diversity of the workforce and this can lead to a perception that under-represented groups have an advantage,” said Barrington.

“However, most engineers are primarily focussed on problem solving and will work well with anyone that shares their enthusiasm.”

For Muram Abadi, who started her masters in aerospace engineering, felt as though women had to “go an extra mile” to succeed, and believes this act of sexism plays a big part in the motivation of female engineering students at KU.

“If a white male can do it why can’t I? Every time we go up a year I look around and think, what’s the difference between him and I? We both got here, we are both in the same position.”