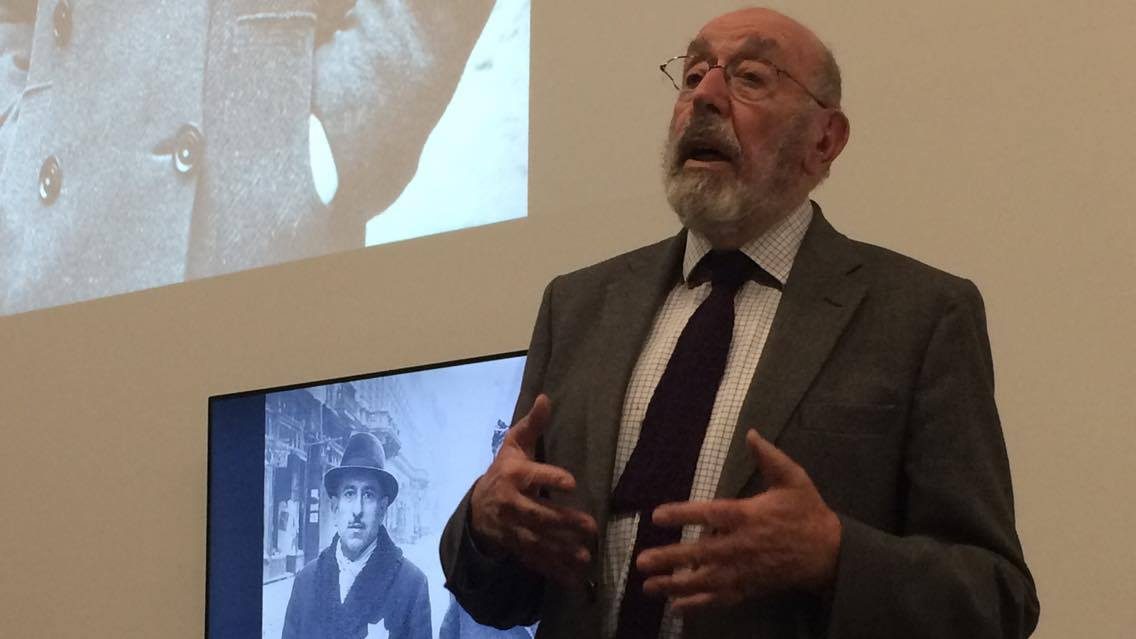

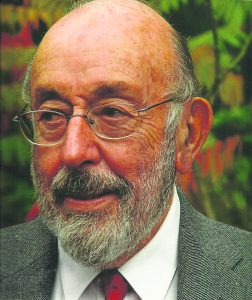

The audience could hear a pin drop in the Jacqueline Wilson hall as Holocaust survivor John Dobai spoke of how he and his family escaped the clutches of Nazi Germany.

In the last 10 years, Dobai has travelled across England to keep the memory of his two aunts and cousin who were gassed to death in Auschwitz during World War II.

He said he does this to point out the evil of discrimination and to emphasise that it is still here today.

“Every time I tell the story I remember the people and the family who were murdered,” said Dobai, 83.

“My cousin, my two aunts and from the wider family two grandfathers. But I also remember our friends and neighbours and all the people of Budapest and Hungary and all the other people who were murdered.”

When the first Anti-Semitic laws were passed in Hungary, Dobai’s parents converted to Roman Catholicism, thinking that higher integration would save them from being identified as Jewish, but nothing could be done to escape the horror.

Raised as a Roman Catholic, Dobai had no idea he was Jewish until he was supposed to return to school after Easter holiday when a classmate said he would not be able to go back because he was a “dirty, stinking Jew”.

“I felt destroyed,” said Dobai. “I cried for hours when my mom told me I was Jewish.”

Dobai’s father fought for Hungary in World War I and was summoned for army service, but was denied entry because he was Jewish. Instead, he was sent to do slave labour for almost three years, leaving Dobai and his mother alone in Budapest.

In a desperate attempt to save her son, Dobai’s mother even sent him to live with a peasant family, but when he caught chicken pox they gave him back to his mother.

She then sent him to a boy’s home, where he was returned from illness again. Three days after his departure, all Jewish boys in the home were shot dead.

Dobai’s father was later released from slave labour and miraculously managed to track down his wife and son.

He had heard of a man named Raoul Wallenberg, who offered Swedish passports and a home in Budapest that was under protection of the Swedish government. He applied for the passports and the family stayed there.

Although it was considered a safe space, the house had no gas and little water.

Wallenberg left to bring food to the 600 people who lived there, but never returned; it wasn’t until years later that Dobai learned that Wallenberg had been shot and killed under Stalin’s order in 1947.

“They weren’t murdered because they did something wrong. They were just people who the Nazis and Allies decided were inferior people,” said Dobai. “We don’t talk about people in a mass, we differentiate.

“Yesterday, Donald Trump declared that the citizens of seven countries can’t go to the United States. He didn’t differentiate between one or the other.

“They are citizens of that country. To condemn an entire people without reference of their individuality, I think it’s awful and we should fight against it. That’s what I’m trying to hand on, so that we are aware.”

Dobai mentioned that he saw two benches last week near his house with the words “the Holocaust is a lie” written on them.

“Anti-Semitism is not dead,” he said.

Raoul Wallenberg saved the lives of hundreds of Jews in Hungary and Dobai visits his statue every January to leave flowers.

“He was a good man,” he said, “I just want to say thank you.”